UEA Live event: Marina Warner in conversation with Sophie Herxheimer

Written exclusively for UEA Live, by UEA LDC student Melis Erdem

On the evening of Wednesday 28th April, I had the pleasure of attending feminist critic and author Marina Warner’s conversation with illustrator and poet Sophie Herxheimer. I had never encountered either writer before; following this event, however, I felt fortunate to have engaged with such inspiring, creative individuals. The interplay between drawing and words in Inventory of a Life Mislaid provided rich material for discussion, as did the artists’ joint heritage of post-war immigration.

As an audience member, I was distinctively amazed at the life Warner has led so far, and the creative projects she continues to pursue. Born in England, she emigrated with her parents to Cario as a child (lots of her family’s experiences in Egypt features in her memoir). As the author of several short stories, as well as many non-fiction works on feminism and mythology, Marina Warner spoke with confidence, intelligence, and eloquence. I was captivated by the whole discussion and frequently felt the urge to chip in to express my enjoyment.

Sophie Herxheimer and ‘the shoes’

I was interested to explore the photographed collection of objects from her family history – such as a hatbox, a cigarette tin, and a pair of perfectly preserved leather brogues. These items aided the imaginative retelling of Warner’s mother’s journey from Southern Italy to post-war England, and later to Egypt. However, when I first saw these antiques, I struggled to recognise anything inspiring or interesting about them. I found myself questioning my creative abilities as a writer since they had provided so much inventive fuel for both Warner and Herxheimer. However, once I had observed the artists’ methods for translating the past into the present, I realised that patience and noticing were crucial in this creative process. The writers had worked in conjunction to uncover the relics’ magic, drawing and writing in response to each one. I felt encouraged to look closer and unpick the objects’ mysteries as they had. After my initial frustration, I could better appreciate each one’s journey and significance, instead of noting them at face value. As Warner commented, “if you spend time with an object, it will tell its story.” Once I saw the shoes, cigarette tin, and the roll of film as “talismans” of inspiration instead of just objects, I better understood how the artists worked with their source material.

A central backbone of Warner and Herxheimer’s work on this memoir concerned the past and memory. The author admitted there was a kind of “exposure” involved when writing this memoir, as it focuses on her family’s personal history; “a novel is a camouflage. This novel is very exposed.” I felt this was perfectly captured in one of the objects, an unimposing metal canister. It contained both the burning of Cario in the 1952 protests and Warner’s mother’s wedding day in two rolls of film. Marina commented that for her father, this canister brought together two “poles of his life.” Mr. Warner’s bookshop in Cairo was burnt down in the uprising, which his daughter recounted in an impactful excerpt from her memoir. I felt the author “exposed” a beautifully gentle moment of connection between herself and her mother in their family home, moments before the protests began. Warner crafted the verbal equivalent of a photograph, evoking a vignette that captured a time gone by. The contrast between peace and discord in her early childhood memory was a poignant reminder of the political tensions which structured Mr. and Mrs. Warner’s post-war lives. I recognised the process of accepting your parents as people with history, stories, and secrets that existed before you did, and therefore found Warner’s honesty and vulnerability humbling.

Alison Winch, Marina Warner and Sophie Herxheimer

An interesting aspect of this memoir was a wartime-era woman’s story was expressed via a post-war woman writer. Drawing on her affinity for fairy tales, Warner reflected on how her mother underwent a sort of transformation into an “English countrywoman” – something akin to Cinderella, but arguably with more struggle. Marina commented that she rejected her mother’s expectations of beauty and femininity, instead choosing to embrace the second-wave feminist movement of the 1960s. I identify as an intersectional feminist; therefore, it was both humbling and infuriating to hear Marina recall her mother’s insistence that she should “marry a rich man and stay married,” and to “never contradict a man, it’s rude.” I empathised when Warner shared that her mother disapproved of her way of life. Whilst I view Marina’s literary career as incredibly successful, I recognised the generational gap between the two women – maybe Marina was too bold, daring, or outspoken for what Ilia Warner had expected. The author shared that when writing her memoir, she unearthed new facts about her late mother’s life. I felt a pang of sadness to learn about Ilia Warner’s ability to carefully conceal her unhappiness; the fact this behaviour was probably commonplace at the time made it all the more sobering. Therefore, I felt there was something powerful and important in Marina Warner writing her mother’s experience; a post-war writer can express what a wartime-era woman could not.

Sophie Herxheimer’s background as an illustrator and poet added a crucial creative dimension to this novel. Hearing her recite from her poetry collection Velkom to Inklandt was envigorating. The poet’s adopted German accent elevated the content and atmosphere of each piece, which detailed her grandmother’s experience as a “stranger” in this country. Her striking yet wonderfully comedic tone suggested her grandmother’s resilience and determination when acclimatising to a foreign place. I was struck by the similarities in each artist’s family heritage and was interested in how each responded creatively to the past. For Sophie, writing poems in which she inhabited family members was “irresistible” as “writing is a translation from reality.” As someone whose family members have immigrated to Britain, I recognised the sense of bewilderment when entering the unknown, even with experiences as menial as getting the bus. I found Warner and Herxheimer’s words held a poignancy and skill that momentarily transported me to another time. I was surprised to find myself reminiscing on recognisably ‘British’ images of times gone by, as I had not expected to relate so intensely to the world described. Both women’s work encouraged me to consider the European immigrant experience of alienation, as I realised I had approached these scenes as someone familiar with British culture. Journeying into unknown territories was massively disorientating for the artists’ family members, but both communicated their ability to survive, adapt, and become a member of their new country.

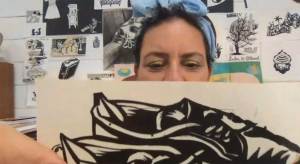

As a university student, I have often worried about how to conflate art with a paid career. However, I experienced a surge of confidence after experiencing Sophie Herxheimer’s vibrant, enthusiastic energy. Surrounded by a collage of black and white lino prints, the illustrator’s passion for her work was almost tangible. In response to an audience question about a typical day in the studio, Herxheimer emphasised her creative experimentation. Given the freedom to create, she “harnessed the unconscious” by experimenting with words and images until she arrived at the finished project. I was fascinated by her process of being led by unrestrained creativity, and approaching projects as adventures to be explored. Herxheimer compared her artistic task to an orchestra conductor. I particularly enjoyed this metaphor, as the “schemas” Herxheimer created enabled her to map out ideas on pieces of paper, providing a visual beginning, middle, and end. This method allowed the reader to progress through the book via a mix of words and images. Herxheimer commented that she aimed to “match the landscape of [Marina’s] writing.” This is reflected in the bold yet elegant line prints that accompany the novel.

The pair of perfectly preserved leather brogues, for example, reappeared printed upside down against a map. This mirrored the confusion and disorientation which accompanied the memoir’s emotional core. Having previously worked together on a collection of fairy tales, the artists seemed to understand what the other wanted to achieve or communicate. Mutual trust and respect between the two women was clear – a collaboration of artistic mediums enabled the project to come to fruition.

Sophie Herxheimer | Credit: John Stuttle

Herxheimer’s decision to cut up and use vintage tourist brochures written about 1930s-40s Egypt was immensely satisfying. She subverted apparent objectivity and challenged the inherently colonial and Eurocentric mindset they were written with. I found the artists’ passion for discussing politics invigorating as neither artist shied away from having ‘difficult’ conversations. I admired how both firmly agreed that “the truth needs defending,” given the “deliberate desire to deceive.” Marina commented that she sees “seeds in the pre-Suez world […] re-emerging” in the present. As a young person experiencing rising far-right nationalism, the impact of a climate crisis, and a global pandemic, I was struck by this comment. For a while afterwards, I found myself considering the implications of this statement, and felt inspired to question how British authorities exerted colonial power over Egypt. The author invited us to examine “television reconstructions” of British brilliance in media, and the power relations between the two states. As Warner asked, why does England choose to continuously export, or exploit, goods from a distant foreign country, instead of a closer one such as Belgium? I found these discussions very stimulating, stand hugely enjoyed considering the mess between reality and truth.

Hearing Marina Warner and Sophie Herxheimer in conversation was extremely insightful, interesting, and enlightening. I came away considering the necessity of asserting yourself as an international, keeping the memory of who you are, and where you come from. Inventory of a Life Mislaid captures this experience beautifully through a collaboration of imagination, memory, and visual art. This evening was perfectly summed up, I felt, in a line from Sophie Herxheimer’s poem; “this city will be home.”

Melis Erdem (she/they), is an English Literature with Creative Writing student entering her third year of undergraduate study. They enjoy experimental writing and exploring the possibilities of form, language and words. At the moment, she is very interested in the interplay between politics and art, and is working towards a creative dissertation incorporating current affairs, feminism, and visual art. In the future, they hope to pursue a creative career, such as an author, editor, and scriptwriter.

Image credit:

Header Image: Dan Welldon