Masculinity, Sex and Oranges: ‘Raven Smith’s Men’

Written for UEA Live by Ruby Skippings

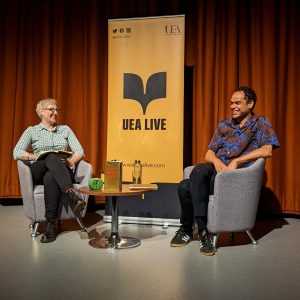

Sarah Godfrey and Raven Smith at UEA Live

Raven Smith – British Vogue columnist, cultural commentator, and critically acclaimed author – was recently dubbed “the funniest person on Instagram” by Sonder and Tell. It’s fair praise. From the get-go, the evening’s discussion, lead by UEA professor Dr Sarah Godfrey, was thoroughly entertaining. After Sarah’s introduction to the book, Raven Smith’s Men, Raven humbly teased “Good to know you enjoyed it”. The comedic tone never let up. I was sat at the very back of the lecture theatre, and Raven’s infectious laugh travelled across the room.

This is Raven’s second publication after his debut book Trivial Pursuits, a Sunday Times bestseller that came out three weeks into lockdown. Published in April of this year, Raven Smith’s Men has received rave reviews and is now available to listen to (read by Raven himself) chapter-by-chapter on BBC Sounds. It’s a memoir, an examination of the highs and lows of masculinity as told through Raven’s stories of the men that have influenced him. Sarah aptly describes it as a journey: not a critique of masculinity, but also not a defense. Raven opens his reading with “Here in lie the men of Raven Smith.” This is entirely accurate. During the rest of the evening, we came to learn that the book is simply an observation of these men, rather than an attempt to resurrect or crucify them. He lets them be.

The key thing, it seems, is that these men are not specific. He met them in an array of places – work, socialising, even school – and they played different roles in his life, whether that be family, romantic or sexual. They are “Stepdads, actual dads and some wanted to be called Daddy”. Raven joked that he’s disappointed in one of the jokes and only spotted it after. This is what makes the book so quintessentially human; Raven wanted honesty to stay at the centre of his writing. He said we all have our men, it’s just that a lot of his were memorable.

Raven described himself as “obsessed” with men, as he is a man and is attracted to them. A lot of Raven’s identity is

woven into this book; part of what inspired him was an Observer article he wrote about his dad and race. As a mixed race and gay man, he admitted to having felt like he didn’t ‘belong’ for much of his childhood. But he’s not sure how many battles he has left in terms of battling racism and homophobia, so the topic of masculinity came naturally. It’s a hugely influential concept, but one that Raven didn’t feel he needed to examine at large. Instead, he examined it through the men that were once, or are still, important to him.

Toxic masculinity is an undoubtedly important to write about, especially on an emotional level – Raven profoundly

pointed out “When someone keeps saying ‘boys don’t cry’, it does something to your psyche after a while”. But he doesn’t claim to have all the answers, and that’s why the book is left without a strict conclusion. He admits to policing his own gender, in the jokey context of a shirt he thought was too feminine. In the periphery of being a man, there is more room in which to break gender norms. Raven and Sarah discuss the memoir as a playful approach to the limitations of gender identity, but it’s obvious how important it is to Raven that male readers are conscious of these limitations, in a book that actively excludes women. He was apologetic about this and called the women in his life “the best thing that ever happened to me”.

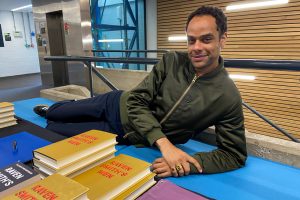

Raven Smith at UEA Live

Despite the obvious appeal of telling everyone that the memoir is a nuanced, veiled critique of what defines a man, Raven just doesn’t see it like that. He told Sarah “No, it’s not a formulaic piece about larger issues of privilege in a patriarchal world”. That doesn’t mean it’s had any less of a response. Readers were moved by the chapter on his stepdad. He wanted him to come across as a “gentle man: that’s it”. Sarah pointed out that his voice comes across enigmatically, and Raven joked that it’s due to his unusual name. There might be truth in this. After all, the book is about the experiences that define us.

Both Raven and his book have liminality: “a foot in both places” as Sarah put it. This launched an interesting discussion about Raven’s more empathetic, ‘feminine’ attitude compared to his husband’s problem-solving mind. Raven confessed that he, as a writer, has a habit of over-analysing, but joked about the gender politics of hiring a female cleaner vs a male one (who he worries would be too attractive). The conversation did this a lot – seemingly steer away from the topic of the book – but all the humorous tangents feel truthful to its core message. Rome wasn’t built in a day, and this book isn’t trying to solve toxic masculinity or provide any solutions. The short section on the man who ghosted him, most likely, isn’t meant to be more than a funny anecdote about internet dating. The same can be said about the bit when Raven is hit by an orange. But it leads onto Raven posing a question that I think stuck with the whole audience: who is a footnote in who’s life?

When Sarah asked about Raven’s generation, there was a debate about what is meant. In the “post-AIDs” generation of Raven’s youth, there were more straight people that contracted HIV than gay people. He said that he was a “fucking idiot” in his youth about practicing safe sex, but that’s part of what makes life so absurd and brilliant and interesting – you never have the “aha!” moment you’re waiting for. However, in this generation, there are new branches to masculinity. Incel culture is rampant and born from the internet exposing people to sex but not guaranteeing them to have it. Raven puts it down to radicalisation via an algorithm. Incels aren’t discussed in the book, but something Raven is aware of as an online writer.

When Sarah asked about Raven’s generation, there was a debate about what is meant. In the “post-AIDs” generation of Raven’s youth, there were more straight people that contracted HIV than gay people. He said that he was a “fucking idiot” in his youth about practicing safe sex, but that’s part of what makes life so absurd and brilliant and interesting – you never have the “aha!” moment you’re waiting for. However, in this generation, there are new branches to masculinity. Incel culture is rampant and born from the internet exposing people to sex but not guaranteeing them to have it. Raven puts it down to radicalisation via an algorithm. Incels aren’t discussed in the book, but something Raven is aware of as an online writer.

Interestingly, Raven called himself a “relic” to modern ideas about gender binary – he said he identifies as a man and that won’t change, no matter how “woke” he becomes. He is annoyed at the deterministic ideals of what you have to be as a man, but he’s also annoyed at the idea that masculinity is in crisis. “It’s not bad to be a man; what is bad is the prioritisation of masculine characteristics that result in things like war, instead of looking after one another.” In explaining his success from climbing the capitalistic ladder, Raven, somewhat controversially, joked that he doesn’t see the patriarchy being dismantled any time soon. This is all summed up neatly with the idea that “masculinity is never going to be tied up”, and it’s kind of the tone the talk ends on. Raven is not looking for the answers. He’s looking to tell unedited stories with wit and grit, all under the umbrella of manhood. And that’s what he’s done.

An audience member asks how he came up with the men that featured in the book, and Raven answered straightforwardly: “It’s random”. As a funny guy, it’s quite surprising to hear about his own struggles with toxicity. His “bad behaviour” was left in the book despite requests for it to be taken out. The whole point is duality, after all. When asked if he’s going to do more presenting, Raven seemed incredibly keen. He said he felt more confident going into writing his second book but it’s still not an easy process. In the future, he endeavors to do less self-expressing. Clearly, selflessness was on his mind as he discusses looking to have children with his husband.

Raven is a talented writer for many reasons, but a notable one is his desire to push himself; to write in a way that is challenging. Balancing amusing and serious, Raven Smith’s Men achieves that. He might need a break, though. When asked what he’s up to next, he immediately answered “going on holiday”.

Ruby Skippings is a third year English with Creative Writing student whose guilty pleasures include cheesy music, cake and buying more books than anyone ever needs. In her spare time, she makes films with friends, attends dance sessions and plays Cluedo with anyone who will join in.