A Reflection on 20 Years of Bad Blood

Sharon Tolaini-Sage, daughter of Lorna Sage, reflects on her mother's seminal memoir 'Bad Blood', to celebrate its 20th anniversary

Written exclusively for UEA Live and The British Archive for Contemporary Writing by Sharon Tolaini-Sage.

Bad Blood can be viewed through a kaleidoscopic range of lenses: social document, a version of pastoral, detective story, hymn to education – a story about class, gender, sex and feminism, full of reversals, but also full of humour, resilience, grit and joy. Even, through a favourite lens of my own, subverted Western: Glamorous outsider heroine rides into a one-horse town riven by inequality and presided over by an endless cycle of social immobility. When she rides out, having written it up and torn it open to the world, she implies future battles, in other unequal microcosms of the world.

Lorna in 1996, the lone woman in a line up of Deans at UEA | Source: Sharon Tolaini Sage | Copyright: UEA

This may not be (no, definitely is not) how Lorna viewed her memoir, but she clearly used ‘writing up the past’ – a special, hard-won power – as a retrospective way of making it right. Like all good Westerns, it tells a universal human story. As Kathryn Hughes said in her introduction to the 10th anniversary edition: ‘Few of Sage’s readers will have experienced any of this at first hand, yet her extraordinary achievement is to make us feel that this story is somehow ours too’. At 20, Bad Blood is just coming of age, and it has much to say to a contemporary audience. A young friend of my daughter’s, Marianne, who mentioned reading the book for the first time, found that it instantly transported her back to the sensations of her own childhood, and the playground life of her Catholic school.

Lorna had, as she mentioned in a letter to her publisher dated September 1991: ‘…set out from the idea of the past as another place…’. But it turns out for me at least, that looking back provides an extra layer of irony, revealing how the past and the present are often separated by less of a gulf than we might suppose.

Bad Blood has an uncanny ability to show that while in some ways (whale meat stew for school dinners) the past might seem remote and particular, in others (Mr Palmer the schoolmaster’s lesson in knowing your place) we have not travelled as far from it as we might think. The book manages to pivot between looking back and standing firmly, critically, in the present, (whenever that might be) so the present gets called into question, just as much as the past. Lorna’s voice speaks clearly to now.

In my teaching life, I have heard more than one young woman describe their teacher discouraging them from going to university because, well, there was no point – contemporary Mr Palmers, who pronounce on the pointlessness of most of their pupils’ desires to be anything other than ‘muck-shovellers’.

Along with taking stubborn refuge in books, what Lorna described as her own ‘bloody mindedness’ enabled her to resist the path that time and place dictated. That it was truly discombobulating to the world she was in battle with can be seen in some of the artefacts currently on loan to the Archive at UEA.

Source: Sharon Tolaini-Sage

The envelope in which she was sent her A level certificates, for example, is addressed to an impossible, hybrid ‘character’ – Miss Lorna Sage. Lorna had been Miss Lorna Stockton, a schoolgirl who had to leave, marry, to become Mrs Lorna Sage, and take her ‘A’ levels outside the system. But this identity, of married woman, still educating herself and passing her A levels, clearly wouldn’t compute for the authorities sending her the proofs of her success. Lorna was furious at the time that the machine of authority was incapable of acknowledging her as herself. She continued to rail against it when she got her first job at UEA as a lecturer, but couldn’t pay her own taxes, and had to do so through my father.

The coverage that ‘The Sages’ received in the press on getting their degrees, shows just how extraordinary it was that Lorna should have been married (with a quite grown-up ‘baby’) and have graduated. In a boiling summer, punning headlines (‘It’s all a matter of degrees’ and ‘The Couple Who Are One Degree Over’) in the Daily Mirror and Daily Mail emphasise how far they were outside the norm. The best (or worst) of all of these from the Daily Mail, June 27th, 1964, reads: ‘The only marriage where honours are even…’

Contemporary young women, who might not be aware of how recent and precarious their rights are, would be really interested to know that married women had only just been allowed entrance into university. Lorna’s generation – the first to go to university in a period of subtle but momentous class shifts in English/Welsh society – are completely recognisable in our turbulent contemporary landscape. Women having babies now find themselves shocked to belong to a group who can be suddenly, magically invisible, and Shropshire is still proving to be a dangerous, ‘un-place’ for those giving birth. So many of a woman’s freedoms to have moved out of the domestic sphere and into the world as actors, each in their own right, can be undone in a trice, flattened by seemingly innocuous change, such as the recent virtuous lure of ‘working from home’.

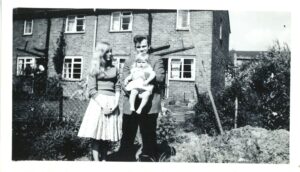

‘The delinquent kids and their kid’, Lorna, Vic and Sharon in 1960 | Source: Sharon Tolaini-Sage | Copyright: Victor Sage

In the photo that Lorna entitled ‘the delinquent kids and their kid’, taken at the back of my grandmother Sage’s council house, Lorna and Vic look what Lorna described as ‘…v. 1950’s still…’ but ironically I see the image as having a contemporary energy. Their future was all ahead of them, and I think of it as an inspiration and a cue for bloody-mindedness in a contemporary reader, who might see Bad Blood as a call to resist the power of time and place to hold them back.

Sharon Tolaini-Sage is the daughter of Lorna and Victor Sage. In addition to being a member of the Games Art and Design teaching team at Norwich University of the Arts, she is a translator and writer on design for Pulp, an Italian imprint of Eye Magazine. In 2017 she was appointed an ambassador for the not-for-profit organisation Women in Games, whose primary objective is to double female participation in the games industry by 2027.

Sharon will be discussing ‘Bad Blood’ with Victor Sage, her father, and acclaimed author Louise Doughty at UEA Live on Wednesday 11 November.